World’s youngest ever women’s chess champion: “I’m just a normal teenager”

侯逸凡 (Hóu Yìfán), the 16-year-old chess prodigy, tells Peter Foster about training, travelling — and Oliver Twist.

侯逸凡 (Hóu Yìfán), the 16-year-old chess prodigy, tells Peter Foster about training, travelling — and Oliver Twist.

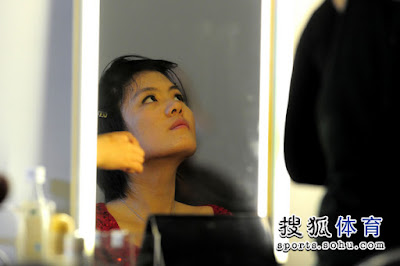

侯逸凡 (Hóu Yìfán). Photo: Katharina Hesse.

By Peter Foster, 北京 (Běijīng)

The Telegraph, January 29, 2011

There is nothing in the slightest bit ordinary about the achievements of 侯逸凡 (Hóu Yìfán), the Chinese chess prodigy who stunned the world just before Christmas by becoming the youngest ever women’s world chess champion at the age of just 16.

And yet, in appearance at least, it is a quintessentially ordinary Chinese teenager that shuffles in through the door at the Chinese Chess Association in 北京 (Běijīng), feet clad in Nike trainers, colourful scarf draped around her neck and a trendy purple beret holding back neatly bobbed hair.

As her mother looks on, Miss 侯 (Hóu) greets us with a bright but bashful smile and an easy-going “hiya” showing off the English language skills she’s picked up from her travels on the international chess circuit where she has been playing since the age of nine.

The story of Miss 侯 (Hóu)’s ascent to the upper echelons of world chess is both the chronicle of single-minded ambition and the everyday tale of a Chinese only child born to hardworking parents who would sacrifice everything for their child’s achievements.

Miss 侯 (Hóu) is both a genius – she became the youngest ever female chess grandmaster at the age of 14, earlier even than her hero Bobby Fischer — and a typical Chinese teenager who, like millions of nameless others, has worked almost unimaginably hard to make the most of her talents and opportunities.

But asked the sacrifices required for her daughter’s success, Miss 侯 (Hóu)’s mother, a 42-year-old nurse, chooses to stress the ordinariness of her daughter’s start in the provincial city of 兴化 (Xīnghuà), 200 miles north of 上海 Shànghǎi where her father was an official in the local justice department.

“We weren’t rich, but we weren’t poor either”, says 王茜 (Wáng Qiàn), “but you will have heard of China’s one-child policy, and like every other parent we were always thinking of ways of to improve our child’s development”.

“There was no dream or great plan, but one day when 逸凡 (Yìfán) was aged five a neighbour’s older child taught her how to play draughts (checkers). After only being taught once, 逸凡 (Yìfán) was winning easily against the older child, so we decided to pick on board-games to broaden her thinking”.

“We took her to a local games club but she always showed fascination in the Western pieces, the horses and the castles”, adds Mrs 王 (Wáng), “so we decided that chess was the one for her. But back then it was only about broadening her mind, and helping her education, we never dreamed we would come so far”.

By the age of seven, aided by the extra night shifts worked by her mother to free up time to guide her daughter, Miss 侯 (Hóu) had already outgrown her local chess club in 兴化 (Xīnghuà) and the family moved north to 山东省 (Shāndōng province) where a bigger club helped with coaching and living expenses.

At that age she attended a full day at school, came home to complete her homework and then at 5pm went to played chess, sometimes for five or six hours at a stretch, although Miss 侯 (Hóu) herself says it never seemed that long.

“I had such an interest in the game, a passion you could say, that meant I never got bored with it. I never tried to get out of playing. I think that is what has helped me succeed, I always wanted to keep playing, to keep learning more”, she says.

She dismisses the suggestion that her mother was a “Tigermom” in the mould of 蔡美儿 (Amy Chua), the Yale Law professor, whose unapologetic paeon to tough Chinese parenting, “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior” caused such furore recently.

“My parents always gave me a choice about playing, but they said that if I wanted to play chess, then I should focus on it completely”, she says, adding that such attitudes and parental expectations are simply the norm for Chinese children. The difference is her success.

“I also have my other studies and I still have some time to do other things, like swimming, listening to music and reading books. I love to read. I recently just finished Oliver Twist for my English studies which is a great book”.

Miss 侯 (Hóu) says that her sheer love for the game protected her from the stress that, according to a joint Chinese-UK study published in the British Medical Association’s Archives of Disease in Childhood journal last year, afflicts about a third of primary school age children in China.

Success also helps makes sense of the sacrifices — she won $60,000 for winning the world championship and the 山东 (Shāndōng) government have verbally pledged to give her family a new house — although Miss 侯 (Hóu) says she doesn’t play for money, but to win.

“Half the money went to the federation, some more in tax and anyway I have it all to my parents. If I need something I just ask. After the world championship I asked for a new, faster computer as my old one was too slow for the best chess programs”.

It was in 山东 (Shāndōng), at the age of nine that Miss 侯 (Hóu) came to the attention of China’s national coach, the grandmaster 叶江川 (Yè Jiāngchuān), who recognised the talent of the young girl sitting opposite him when she played him and immediately picked up on almost all his weak moves.

“She had wisdom beyond her years”, he recalled with his protégé safely out of earshot, “she was precocious and an aggressive and fearless player. It was clear to me then that she was a very rare talent”.

Months later in 2004 Miss 侯 (Hóu) was enrolled under 叶 (Yè)’s tutelage at the Chinese Chess Association training program in 北京 (Běijīng) where she continues to build on a talent whose full potential is still many years from being reached.

At just 16, Miss 侯 (Hóu) is already the third-ranked woman player in the world (the world rankings, based on a points system, are separate from the world championship), with many predicting that she will continue to surpass the achievements of the great Hungarian woman player Judit Polgár. Ms Polgár, now 34 and the only woman among the world’s top 100 players according to FIDE, the international chess federation, became a grandmaster at 15 — a record broken by Miss Hou two years ago.

Miss 侯 (Hóu)’s rise, like the rise of China in so many other spheres of life, is not isolated. She is now one of the 10 Chinese players in the women’s top 100, a position unthinkable as recently as 2002 when not a single Chinese woman made the elite list.

But Miss 侯 (Hóu)’s sights are set higher than becoming the world’s best female player, with ambitions to take on the very best male players, emulating her hero Bobby Fischer whose games against the Soviet Union’s Boris Spassky she studies for her own training.

“Traditionally women have not beaten the best men”, adds coach 叶 (Yè), “but 侯 (Hóu) has the potential to rival the best men. Chess is a game based on military tactics and stategy, so it has always appealed more to men. You need to have a strong, aggressive desire, but she 侯 (Hóu) has that. Now only time and hard work will tell”.

Ask Miss 侯 (Hóu) herself and she seems slightly embarrassed by such talk, offering an answer of typically Chinese mix of self-deprecation and Confucian piety. “I think I will just keep working, follow my parents’ advice and keep playing my chess and let nature take its course. That is how I achieved my current status”.

But 刘伟 (Liú Wěi), the manager of the 山东 (Shāndōng) chess club where Miss 侯 (Hóu) cut her teeth is more forthcoming, believing Miss 侯 (Hóu) has a unique quality for a woman player that over the next decade could help her to achieve more than any woman chess player in history.

“When you meet her, she’s such a sweet-tempered, good-natured girl. She’s very quiet and straightforward, a bit like her father. But when she plays chess, then she plays with such aggression, she’s like another person. I think this drive and attacking spirit comes from her mother”.

As so often in China, in the end, it all comes back to the parents.

The Telegraph, January 29, 2011

There is nothing in the slightest bit ordinary about the achievements of 侯逸凡 (Hóu Yìfán), the Chinese chess prodigy who stunned the world just before Christmas by becoming the youngest ever women’s world chess champion at the age of just 16.

And yet, in appearance at least, it is a quintessentially ordinary Chinese teenager that shuffles in through the door at the Chinese Chess Association in 北京 (Běijīng), feet clad in Nike trainers, colourful scarf draped around her neck and a trendy purple beret holding back neatly bobbed hair.

As her mother looks on, Miss 侯 (Hóu) greets us with a bright but bashful smile and an easy-going “hiya” showing off the English language skills she’s picked up from her travels on the international chess circuit where she has been playing since the age of nine.

The story of Miss 侯 (Hóu)’s ascent to the upper echelons of world chess is both the chronicle of single-minded ambition and the everyday tale of a Chinese only child born to hardworking parents who would sacrifice everything for their child’s achievements.

Miss 侯 (Hóu) is both a genius – she became the youngest ever female chess grandmaster at the age of 14, earlier even than her hero Bobby Fischer — and a typical Chinese teenager who, like millions of nameless others, has worked almost unimaginably hard to make the most of her talents and opportunities.

But asked the sacrifices required for her daughter’s success, Miss 侯 (Hóu)’s mother, a 42-year-old nurse, chooses to stress the ordinariness of her daughter’s start in the provincial city of 兴化 (Xīnghuà), 200 miles north of 上海 Shànghǎi where her father was an official in the local justice department.

“We weren’t rich, but we weren’t poor either”, says 王茜 (Wáng Qiàn), “but you will have heard of China’s one-child policy, and like every other parent we were always thinking of ways of to improve our child’s development”.

“There was no dream or great plan, but one day when 逸凡 (Yìfán) was aged five a neighbour’s older child taught her how to play draughts (checkers). After only being taught once, 逸凡 (Yìfán) was winning easily against the older child, so we decided to pick on board-games to broaden her thinking”.

“We took her to a local games club but she always showed fascination in the Western pieces, the horses and the castles”, adds Mrs 王 (Wáng), “so we decided that chess was the one for her. But back then it was only about broadening her mind, and helping her education, we never dreamed we would come so far”.

By the age of seven, aided by the extra night shifts worked by her mother to free up time to guide her daughter, Miss 侯 (Hóu) had already outgrown her local chess club in 兴化 (Xīnghuà) and the family moved north to 山东省 (Shāndōng province) where a bigger club helped with coaching and living expenses.

At that age she attended a full day at school, came home to complete her homework and then at 5pm went to played chess, sometimes for five or six hours at a stretch, although Miss 侯 (Hóu) herself says it never seemed that long.

“I had such an interest in the game, a passion you could say, that meant I never got bored with it. I never tried to get out of playing. I think that is what has helped me succeed, I always wanted to keep playing, to keep learning more”, she says.

She dismisses the suggestion that her mother was a “Tigermom” in the mould of 蔡美儿 (Amy Chua), the Yale Law professor, whose unapologetic paeon to tough Chinese parenting, “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior” caused such furore recently.

“My parents always gave me a choice about playing, but they said that if I wanted to play chess, then I should focus on it completely”, she says, adding that such attitudes and parental expectations are simply the norm for Chinese children. The difference is her success.

“I also have my other studies and I still have some time to do other things, like swimming, listening to music and reading books. I love to read. I recently just finished Oliver Twist for my English studies which is a great book”.

Miss 侯 (Hóu) says that her sheer love for the game protected her from the stress that, according to a joint Chinese-UK study published in the British Medical Association’s Archives of Disease in Childhood journal last year, afflicts about a third of primary school age children in China.

Success also helps makes sense of the sacrifices — she won $60,000 for winning the world championship and the 山东 (Shāndōng) government have verbally pledged to give her family a new house — although Miss 侯 (Hóu) says she doesn’t play for money, but to win.

“Half the money went to the federation, some more in tax and anyway I have it all to my parents. If I need something I just ask. After the world championship I asked for a new, faster computer as my old one was too slow for the best chess programs”.

It was in 山东 (Shāndōng), at the age of nine that Miss 侯 (Hóu) came to the attention of China’s national coach, the grandmaster 叶江川 (Yè Jiāngchuān), who recognised the talent of the young girl sitting opposite him when she played him and immediately picked up on almost all his weak moves.

“She had wisdom beyond her years”, he recalled with his protégé safely out of earshot, “she was precocious and an aggressive and fearless player. It was clear to me then that she was a very rare talent”.

Months later in 2004 Miss 侯 (Hóu) was enrolled under 叶 (Yè)’s tutelage at the Chinese Chess Association training program in 北京 (Běijīng) where she continues to build on a talent whose full potential is still many years from being reached.

At just 16, Miss 侯 (Hóu) is already the third-ranked woman player in the world (the world rankings, based on a points system, are separate from the world championship), with many predicting that she will continue to surpass the achievements of the great Hungarian woman player Judit Polgár. Ms Polgár, now 34 and the only woman among the world’s top 100 players according to FIDE, the international chess federation, became a grandmaster at 15 — a record broken by Miss Hou two years ago.

Miss 侯 (Hóu)’s rise, like the rise of China in so many other spheres of life, is not isolated. She is now one of the 10 Chinese players in the women’s top 100, a position unthinkable as recently as 2002 when not a single Chinese woman made the elite list.

But Miss 侯 (Hóu)’s sights are set higher than becoming the world’s best female player, with ambitions to take on the very best male players, emulating her hero Bobby Fischer whose games against the Soviet Union’s Boris Spassky she studies for her own training.

“Traditionally women have not beaten the best men”, adds coach 叶 (Yè), “but 侯 (Hóu) has the potential to rival the best men. Chess is a game based on military tactics and stategy, so it has always appealed more to men. You need to have a strong, aggressive desire, but she 侯 (Hóu) has that. Now only time and hard work will tell”.

Ask Miss 侯 (Hóu) herself and she seems slightly embarrassed by such talk, offering an answer of typically Chinese mix of self-deprecation and Confucian piety. “I think I will just keep working, follow my parents’ advice and keep playing my chess and let nature take its course. That is how I achieved my current status”.

But 刘伟 (Liú Wěi), the manager of the 山东 (Shāndōng) chess club where Miss 侯 (Hóu) cut her teeth is more forthcoming, believing Miss 侯 (Hóu) has a unique quality for a woman player that over the next decade could help her to achieve more than any woman chess player in history.

“When you meet her, she’s such a sweet-tempered, good-natured girl. She’s very quiet and straightforward, a bit like her father. But when she plays chess, then she plays with such aggression, she’s like another person. I think this drive and attacking spirit comes from her mother”.

As so often in China, in the end, it all comes back to the parents.

![[ L. Portisch – V. Hort; 7ª del match; Magonza, 16 agosto 2006; rbnqbknr/pppppppp/8/8/8/8/PPPPPPPP/RBNQBKNR; Posizione 520 ]](https://4.bp.blogspot.com/_9K724qHu96M/TULkxFBfb5I/AAAAAAAAAso/HysvWNsL1wY/s320/portisch_hort.png)

![[ Venice, autumn 1971. From left: Roberto Cosulich, Lubomir Kavalek, Sergio Mariotti, and Heikki Westerinen ]](https://3.bp.blogspot.com/_9K724qHu96M/TSGg98BQZXI/AAAAAAAAAsA/6Odw8B0jQeY/s400/Venezia1971.jpg)